How Inventive Step Is Evaluated Globally: India vs. Europe vs. United States

“Patents are the fuel that drives the engine of innovation.”— Alan D. MacDonald

When you think of patents, novelty usually steals the spotlight. But in reality, the biggest hurdle is usually inventive step, also known as non-obviousness. If a skilled person can easily combine existing knowledge to reach your invention, it simply isn’t patentable. This requirement stops people from patenting minor tweaks and ensures only real advancements get protection.

Whether you’re an inventor, startup founder, or simply curious about how patents work, understanding how different countries evaluate inventive step can help you build stronger patent applications. Let’s explore how India, Europe, and the United States approach it and why these differences matter for inventors.

What is inventive step?

At a high level, the test asks:

If someone skilled in the relevant technology had seen all existing public information (the “prior art”), would your invention still strike them as non-obvious?

It’s a subjective test, but each jurisdiction provides a framework to make it more structured.

India — Section 2(1)(ja) of the Patents Act

In India, the statutory definition of inventive step comes from Section 2(1)(ja) of the Patents Act:

A feature of an invention that involves technical advancement or economic significance, or both, and makes the invention not obvious to a person skilled in the art.

Two important take-aways:

- Technical advance or economic significance: Unlike some jurisdictions that focus purely on “technical” novelty, India allows economic benefit (cost-saving, better yields, etc.) itself to support inventive step.

- Objective test via skilled person: The Supreme Court in Bishwanath Prasad Radhey Shyam v. Hindustan Metal Industries held that you must judge obviousness by asking: would a “competent craftsman (or engineer)” with common general knowledge arrive at the invention?

Recent legal flavor

Indian courts also recognize that simplicity does not automatically mean obviousness. In Avery Dennison v. Controller of Patents, the Delhi High Court noted that a seemingly simple modification with “unpredictable advantages” can pass the inventive-step test.

Example

If you redesign a water filter by rearranging known components without solving a real technical problem, it’s obvious. But if you create a membrane giving 2× virus-removal efficiency at the same cost, it can qualify due to both technical advancement and economic impact.

Europe — Problem–Solution Approach under EPC

In Europe, the standard comes from Article 56 of the European Patent Convention (EPC), which says an invention must not be obvious to a “person skilled in the art.”

The EPO uses the Problem–Solution Approach a three-step method:

- determining the “closest prior art”

- establishing the “objective technical problem” to be solved and

- considering whether or not the claimed invention, starting from the closest prior art and the objective technical problem, would have been obvious to the skilled person.

Example

A mobile app automating check-ins via GPS is likely obvious. But an algorithm improving GPS accuracy in low-signal areas offers a technical solution to a technical problem, meeting Europe’s inventive-step bar.

United States — 35 U.S.C. § 103

In the U.S., inventive step is governed by 35 U.S.C. § 103: even if your invention isn’t identically disclosed in prior art, it can be rejected if it would have been obvious to someone skilled in the art.

Two landmark tests dominate U.S. practice:

- Graham Factors (from Graham v. John Deere):

- What is the scope and content of the prior art?

- How does your invention differ?

- What is the level of ordinary skill in the field?

- Are there “secondary considerations” such as commercial success, long-felt need, failure of others?

- KSR v. Teleflex (2007): The Supreme Court introduced more flexibility. If it was “obvious to try” a combination with predictable results, or if combining known elements would be within routine skills, then there’s a risk of obviousness.

Unlike Europe, U.S. law does not require “plausibility” (i.e., showing that the invention is likely to work) in the same way. Courts have rejected plausibility as a substitute for non-obviousness.

Why these differences matter — A few practical scenarios

- Startup deciding where to file: You developed a low-cost sensor that just tweaks a known design but gives 20% better performance. In India, you might lean heavily on economic significance. In Europe, you’d need to show a clear technical bottleneck solved. In the U.S., a detailed prior-art analysis, especially under “obvious to try,” will be crucial.

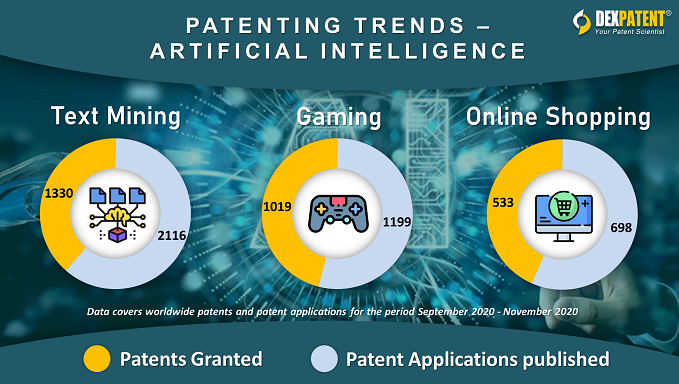

- Software / AI invention: Under EPO’s problem solution approach, you’ll need to argue that your algorithm solves a technical problem (not just a business workflow). Under U.S. law, showing that the combination was not a predictable application of prior art helps defend non-obviousness.

Conclusion

Inventive step may look like a single hurdle — but each major jurisdiction treats it differently:

- India balances technical advancement and economic impact but is tightening standards through recent case law.

- Europe (EPO) applies a disciplined Problem–Solution Approach and demands a technical contribution.

- The U.S. uses flexible, pragmatic reasoning based on prior art, skill level, and real-world factors like “obvious-to-try.”

For inventors filing globally, the lesson is clear: customise your patent application and argument strategy to the legal standards of each region. That’s not just smart — it can make or break your patent grant success.

0 Comments